-Marvin Streich, in The Streich Family

The above quote is from a family history that my mom wrote. Marvin, her eldest cousin, penned several pages of his earliest memories for inclusion in the book. Since he was born in 1934, and his Granny died in 1942, the abovementioned slaughter must have taken place around 1940.

The above quote is from a family history that my mom wrote. Marvin, her eldest cousin, penned several pages of his earliest memories for inclusion in the book. Since he was born in 1934, and his Granny died in 1942, the abovementioned slaughter must have taken place around 1940.I nearly fell off my chair when I first read Marvin's memories. I grew up visiting that same farm, where at one time pigs were killed and boiled and shaved and made into headcheese, but by the time I was born these traditions were defunct, and the recipe and appreciation for Granny's headcheese had been lost. Marvin's childhood memory of the pig was like a passing reference to a kingdom now sunk beneath the sea. These days, reading about headcheese in Larousse or Henderson is a strange, semi-academic exercise, but only sixty years ago my great grandparents were making it from their own pigs.

I recently helped Kevin with some butchering. I left his house with a belly full of pork chops and a cooler full of the two halves of a pig's head. I've collected a few recipes for head over the past year, but I figured my first experiment should be headcheese, in memory of Great Grandma Streich.

Headcheese is a simple but ingenious preparation. The head is cooked in simmering water, so the low, moist heat can break the tough connective tissue into gelatin. After cooking you are left with very tender meat and very rich broth. If you reduce that broth, the gelatin is so concentrated that it sets when chilled (at which point it could be called an aspic). The meat and reduced broth are mixed together, packed into a mold, and chilled to set. The headcheese can then be sliced and eaten.

Recipes tend to be dead simple, usually just a pig's head and aromatics. Often trotters are added to boost the flavour and gelatin content of the broth. A bit of acid helps break down the connective tissue and improves the final taste. Since abattoirs split pigs in half along the spine, my recipe is for a half head.

Headcheese

- half a pig's head

- one trotter

- one carrot

- one stalk celery

- one leek

- one head garlic

- parsley stems, thyme, bay, peppercorns

- splash of vinegar

Pig heads are awkward, with bulky jowls flanking a long snout. They're a bitch to store, which is why Kevin throws them into the oven while he butchers, a simple solution that I think is becoming a beloved tradition. Even working with half a head, my stock pot was nowhere near big enough. I had to break the head into pieces so that it would fit in my two biggest pots. I boned the head so that I could work with the relatively slender skull and a large slab of meat, which could be cut into manageable pieces.

Combine all the ingredients in a pot (or pots...) and cover with cold water. Bring to a boil, then reduce to a simmer, skim, skim, skimming the whole time. Lots of grey foam will form on the surface of the water. After roughly three hours, test the tenderness of the meat. A sharp knife should easily pierce the jowls.

Strain the mixture, reserving the liquid. Discard the vegetables and herbs. Return the broth to the stove and reduce by about half. To test your aspic, put a few tablespoons of the broth into a small bowl or cup and refrigerate. It should set firm and break clean when a finger is dragged through.

While the broth is reducing, pull all the edible bits from the head, which, by the way, doesn't separate conveniently into bones and meat. There are all kinds of other substances, like the snout, which I think is cartilage, but takes on a fantastic, yielding, buttery texture after boiling. Make sure to include stuff like that. When I refer to "meat," below, I am referring to all edible bits collected from the head.

Seasoning is a bit tricky, because the pulled meat and reduced broth have to be salted separately, and because the finished headcheese is served chilled or at room temperature. Season agressively, as the lower eating temperature will mute the salt.

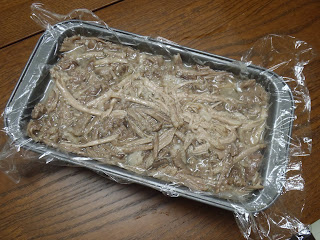

Pack the meat into a terrine or loaf pan lined with plastic wrap. Pour the aspic over the meat. Gently push the meat down to release any air pockets. You can see that this produces a headcheese with a higher meat-factor and lower gelatin-factor than the commercially-produced kind languishing in your supermarket's deli. Let the terrine set in the fridge overnight.

Slice. I prefer to bring mine to room temperature before eating. I finished with black pepper and dried savoury, as I know those flavours were common in Granny's farmhouse. It also benefits from an acidic sauce of, say, chokecherries or highbush cranberries.

You'll notice that my headcheese is a bit grey. If the head were first brined, the final product would have the more familiar pink colour. I wonder if Granny used saltpeter...